Nature often hides its most significant treasures in the most unassuming forms. Along the sandy shores of the Atlantic and the muddy estuaries of Asia, a creature emerges from the surf that looks more like a prehistoric armored tank than a modern animal.

Table of Contents

The Horseshoe Crab is a biological marvel that has witnessed the rise and fall of dinosaurs, survived five mass extinctions, and today serves as an indispensable pillar of the global pharmaceutical industry.

Despite its common name, it is not a true crab at all but a distant relative of spiders and scorpions that has occupied a specialized ecological niche for nearly half a billion years.

In this exhaustive guide, we will unravel the mysteries of this “living fossil,” exploring the Horseshoe crab scientific name, the unique properties of Horseshoe crab blood, and the sophisticated sensory array of Horseshoe crab eyes.

We will also answer critical questions about the Horseshoe crab price, its role in the ecosystem, and how it has managed to remain virtually unchanged since the dawn of time.

Taxonomic Foundations and the Horseshoe Crab Scientific Name

To understand these creatures, one must first look at their place in the tree of life. The systematic classification of these organisms places them within the phylum Arthropoda and the subphylum Chelicerata. Unlike crustaceans, which possess mandibles and antennae, the Horseshoe Crab belongs to the order Xiphosura and is characterized by the presence of chelicerae—specialized appendages used for manipulating food.

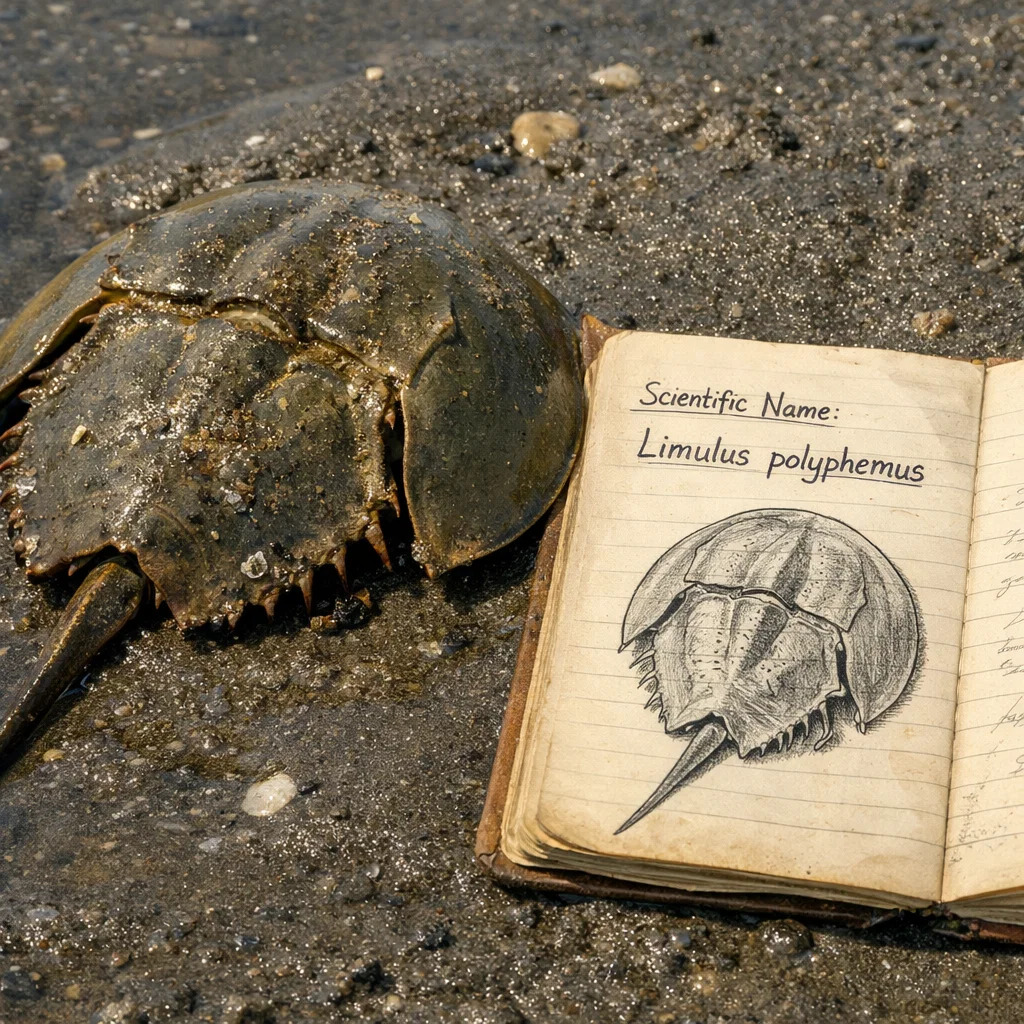

There are four extant species of this animal currently inhabiting the Earth’s oceans, each with a specific Horseshoe crab scientific name and geographic range:

- Limulus polyphemus: Also known as the Atlantic or American Horseshoe Crab, this is the most widely studied species, found along the East Coast of North America and the Gulf of Mexico.

- Tachypleus tridentatus: The Tri-spine species, located across East and Southeast Asia, from Japan to Vietnam.

- Tachypleus gigas: The Coastal species of South and Southeast Asia.

- Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda: The Mangrove species, found in the brackish waters from India to the Philippines.

Genetic investigations reveal that the Atlantic species diverged from its Indo-Pacific relatives millions of years ago. Interestingly, recent genomic sequencing has identified evidence of multiple whole-genome duplication events in their common ancestor, a redundancy that likely provided the evolutionary flexibility needed to develop their complex immune and visual systems.

The Prehistoric Journey: How Did Horseshoe Crabs Survive?

One of the most frequent questions asked by paleontologists and enthusiasts alike is: How did horseshoe crabs survive? While many dominant marine lineages, such as the trilobites, vanished entirely at the end of the Permian period, the ancestors of the modern Horseshoe Crab persisted.

The answer lies in a combination of biological resilience and anatomical “perfection.” The genus Lunataspis, a relative from the Ordovician period (445 to 480 million years ago), displays a tripartite body plan nearly identical to the crabs we see today. This suggests they reached an evolutionary “sweet spot” early on—a configuration so effective for their benthic niche that there was little selective pressure for significant change.

Furthermore, they possess a suite of robust adaptations:

- Respiratory Efficiency: Unlike trilobites, which had a more primitive branchial system, these animals evolved highly efficient “book gills”.

- Environmental Tolerance: They can survive high levels of salinity and varying oxygen concentrations that would be lethal to more sensitive arthropods.

- Mass Extinction Resilience: They have survived all of the “Big Five” mass extinctions, including the Permian-Triassic “Great Dying”.

Anatomy of a Living Fossil: Horseshoe Crab Size and Structure

The physical architecture of the animal is a masterclass in protection. The body is divided into three primary sections: the horseshoe-shaped prosoma (cephalothorax), the hexagonal opisthosoma (abdomen), and the spear-like telson (tail).

The Horseshoe crab size is largely determined by its species and gender, with females typically being larger than males to accommodate their massive egg-laying capacity. The prosoma is the largest section, acting as a rigid chitinous shield that protects the brain and the heart. This shell is periodically shed through a process called ecdysis (molting) as the animal grows. Once the crab reaches sexual maturity, usually between 9 and 12 years of age, this growth ceases entirely.

The Internal Engine

Inside that armored shell is a biological curiosity. Their heart is a long, tubular organ that pumps blue hemolymph throughout the body. Their brain is uniquely shaped like a ring that completely surrounds the esophagus. This means the animal literally “eats through its brain.”

Sensory Complexity: The Secrets of Horseshoe Crab Eyes

While they may appear primitive, the sensory apparatus of these creatures is anything but. One of the most fascinating Horseshoe crab eyes facts is that they possess a total of ten eyes, each specialized for distinct environmental tasks.

| Eye Type | Quantity | Primary Function |

| Lateral Compound Eyes | 2 | Located on the shell; used for mate detection during spawning. |

| Rudimentary Lateral Eyes | 2 | Sensitive to movement and light changes. |

| Median Eyes | 2 | Detect ultraviolet (UV) light and moonlight for lunar tracking. |

| Endoparietal Eye | 1 | Assists in sensing solar and lunar cycles. |

| Ventral Eyes | 2 | Located near the mouth; thought to assist in benthic orientation. |

| Telson Photoreceptors | 1 | Cluster along the tail to synchronize internal clocks. |

The lateral compound eyes are particularly remarkable for their physiological flexibility. During the night, the chemical sensitivity of each individual ommatidium (the units that make up the eye) increases by a factor of roughly 100. This allows the crab to recognize the movement of other crabs in near-total darkness, which is essential for the synchronized mass spawning events that occur during the new and full moons.

Behavior and Protection: Are Horseshoe Crabs Harmless?

A common fear among beachgoers is the spear-like tail of the animal, leading to the question: Are horseshoe crabs harmless? Despite their intimidating appearance, they are entirely docile and possess no venom, stingers, or biting jaws.

The spear, or telson, is a misunderstood mechanical tool. It is not a weapon; rather, it is used as a lever to right the animal if it is flipped over by a wave. Without the telson, a crab stranded on its back would quickly desiccate in the sun or fall prey to shorebirds. The telson also contains the aforementioned photoreceptors that help the crab stay in sync with day-night cycles.

Furthermore, they “chew” with their legs. Lacking teeth or mandibles, they use spiny bases on their five pairs of walking legs, called gnathobases, to grind up food—primarily bivalves and marine worms—as they walk. This macerated food is then pushed into the mouth located on the underside of the body.

The Life Cycle and Horseshoe Crab Lifespan

The journey from a microscopic egg to an armored adult is a long and perilous one. The Horseshoe crab lifespan can exceed 20 years in the wild, though the first decade is spent simply reaching maturity.

The Spawning Ritual

Reproduction is one of nature’s most impressive synchronized events, usually peaking in May and June. Females release pheromones to attract males, who use specialized “clasping claws” (pedipalps) to attach to the female’s shell. The pair then crawls into the intertidal zone. A single female can lay up to 100,000 eggs in a single season, deposited in shallow nests.

Development Stages

- Embryo: Incubates in the sand for 2 to 4 weeks.

- Larva: Known as “trilobite larvae,” they hatch without a tail and settle in shallow nursery flats.

- Juvenile: Over the next 9 years, they molt 16 to 17 times. During this stage, they often swim upside down, using their gills like flippers to forage.

- Adult: Growth stops at maturity, and they move into deeper bay waters and the continental shelf.

The Biomedical Nexus: Why is Horseshoe Crab Blood So Valuable?

The most significant interaction between humans and this species is centered on the unique properties of its blue blood. If you have ever received a vaccine, an IV drip, or an internal medical device like a pacemaker, you likely owe your safety to the Horseshoe Crab.

Why is Horseshoe Crab Blood Blue?

Human blood is red because of iron-based hemoglobin, but Horseshoe crab blood utilizes hemocyanin for oxygen transport. Hemocyanin contains copper, which turns a brilliant, milky blue when it comes into contact with oxygen.

The Magic of the Amebocyte

The true value of the blood lies in its immune cells, called amebocytes. In the 1950s, researcher Frederick Bang discovered that these cells react with extreme sensitivity to bacterial endotoxins (pyrogens) found in the cell walls of Gram-negative bacteria. When these cells encounter even a trace of endotoxin, they release a clotting enzyme that causes the blood to gel instantaneously.

This reaction is the basis for the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) test. Every injectable medication must be tested with LAL to ensure it is free of contamination. The test is so sensitive it can detect toxins at concentrations of one part per trillion.

The “Blue Gold” Economy and the Horseshoe Crab Price

The global reliance on LAL has made this liquid one of the most expensive substances on the planet. The Horseshoe crab price for its blood—often called “blue gold”—is estimated at roughly $15,000 per quart or as much as $60,000 per gallon.

Each year, between 500,000 and 700,000 crabs are harvested from the Atlantic coast to be “milked”. In a laboratory setting, about 30% of the animal’s blood is drained before it is returned to the ocean. While the industry claims this is sustainable, research suggests a mortality rate of 10% to 30% after release. Furthermore, bled crabs often become lethargic and are significantly less likely to participate in the next spawning cycle, which can hinder population growth.

Ecological Interdependence: The Red Knot Connection

The value of these animals extends far beyond human medicine; they are a “keystone species” in the Delaware Bay ecosystem. Their eggs are the primary fuel for the Red Knot, a shorebird that performs a grueling 9,000-mile migration from South America to the Arctic.

The birds time their two-week stopover in the Delaware Bay to coincide perfectly with the peak of the crab spawning. Arriving emaciated, the Red Knots must double their body weight in just 10 to 14 days by gorging on the fat- and protein-rich Horseshoe Crab eggs. Without this precise nutritional boost, the birds cannot survive the final leg of their journey or successfully produce offspring in the Arctic.

Culinary and Cultural Questions: Can Horseshoe Crab Be Eaten?

With their presence in the Indo-Pacific, many wonder: Can horseshoe crab be eaten? In some parts of Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand and Vietnam, they are considered a delicacy. However, consumption comes with significant risks.

While the eggs are the part typically consumed, the Mangrove species (C. rotundicauda) can sometimes contain lethal levels of tetrodotoxin, the same poison found in pufferfish. Furthermore, in the United States, they are primarily used as bait for eel and whelk fisheries rather than human food. Because they are generalist scavengers, their meat is not widely sought after in Western cultures.

Conservation and the Future: The rFC Alternative

The future of the Horseshoe Crab faces a multifaceted threat environment, including overharvesting for bait, habitat destruction from coastal development, and the decoupling of spawning cycles due to climate change.

From Revive & Restore

However, a potential turning point arrived in 2024. The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) officially approved a synthetic alternative to the LAL test, known as Recombinant Factor C (rFC). Produced through genetic engineering, rFC does not require the harvesting of live animals. This shift, which took effect in May 2025, is expected to drastically reduce the biomedical industry’s reliance on wild-caught crabs and could lead to a significant recovery in population numbers.

Frequently Asked Questions Summary

Why is horseshoe crab so valuable?

Their blood contains amebocytes used to create the LAL test, which detects bacterial endotoxins in medical equipment and vaccines. This makes them a cornerstone of modern pharmaceutical safety.

Can horseshoe crab be eaten?

Yes, they are eaten in parts of Asia, but it is risky. Some species carry deadly toxins, and in North America, they are almost exclusively used as bait or for medical bleeding rather than food.

How did horseshoe crabs survive?

They survived through extreme physiological resilience, efficient book gills, and a body plan that reached an evolutionary “sweet spot” 450 million years ago.

Are horseshoe crabs harmless?

Yes. They have no venom, no stingers, and their spear-like tail is only used for flipping themselves over. They do not bite humans.

Protecting an Indispensable Ancient

The Horseshoe Crab is one of the most resilient and indispensable organisms on the planet. From its 450-million-year journey through prehistoric seas to its modern role as the guardian of human health, it is a testament to the power of evolutionary stability.

Whether we are marveling at the ten Horseshoe crab eyes, studying the blue Horseshoe crab blood, or observing their massive Horseshoe crab size during a moonlit spawning event, we must recognize our deep debt to this “living fossil.”

Watch Our Take on the Horse Shoe Crab

As we move toward synthetic alternatives like rFC, we have a unique opportunity to ensure that these ancient drummers of the surf continue to thrive for another 400 million years. Protecting their habitat and supporting sustainable practices through organizations like Petnarianpets is not just an act of conservation; it is a commitment to the biological heritage of our planet. The sand still has its armored visitors, and with the right care, it always will.

Stay wild, stay curious – only on PetNarianPets!

Join The Fun On Instagram, X, Pinterest and YouTube.

Wanna Say Something about animals ? Contact Us.